Marvelous Masonry-Celebrating Masonry’s Heritage: The Historic City of Porto, Portugal

Words: David Biggs, Dr. Barontini, Dr. Oliveira, Dr. Bernardo, Paulo Lourenco, Ana Fonseca, Dr. Poletti, Dora Arenga, Courtney Indart, Catherine CoatsPortugal has emerged as a popular tourist destination. While the country has long been a fascinating destination, a more noticeable surge in international tourism has occurred since 2010. This can be attributed to cultural richness, natural beauty, and affordability.

Portugal has invested in improving its tourism infrastructure, including upgrades to airports, transportation networks, and accommodations. It has also engaged in effective destination marketing and promotion campaigns, showcasing the country's diverse attractions and cultural and historical heritage. Travelers who have visited Portugal share their positive experiences through word of mouth and online reviews, giving Portugal a reputation as a desirable destination.

Portugal has a long and storied history, with influences from various civilizations. Visitors are drawn to its well-preserved historic sites, charming medieval towns, and vibrant cities. The architecture, art, and cultural heritage offer a captivating journey through time. Of course, it also has Marvelous Masonry!

In a previous article, we embraced the medieval city of Guimarães. Here, we travel to historic Porto (also known as Oporto) in northwest Portugal, the country’s second-largest city nestled along the banks of the Douro River and home to world-class port wine produced in the nearby Douro Valley. Porto is a UNESCO World Heritage site with marvelous masonry landmarks such as the Clerigos Tower (Figure 1), which is the tallest bell tower (249 ft) in the city. Human occupation goes back to the 8th century BCE. The Romans named it Portus (for port) in the first century BCE.

UNESCO stated, “The Historic Centre of Oporto, Luiz I Bridge and Monastery of Serra do Pilar with its urban fabric and its many historic buildings bears remarkable testimony to the development over the past thousand years of a European city that looks outward to the sea for its cultural and commercial links.” Furthermore, “The property illustrates over a thousand years of continuous settlement, with successive interventions each leaving their imprints. Individual buildings, such as the rich stock of ecclesiastical properties, are similarly illustrative of this local history.” Porto is rich in history and authenticity.

Porto is in a low seismic zone. However, winds can be extreme, which affects most of the buildings.

Figure 1 – Clerigos Tower c.1763

Figure 1 – Clerigos Tower c.1763

In this article, we’ll highlight two historic religious sites, Porto Cathedral (Sé do Porto in Portuguese) and the Church de São Bento da Vitória. I first visited the cathedral in 2010 and was honored to return in 2023 along with Professor Paulo Lourenco of the University of Minho, who guided the restoration from 2003 to 2008 to view the condition of the cathedral. I visited São Bento da Vitória in 2023 along with a team from the University of Minho during the assessment of the front façade.

Porto Cathedral

Besides being one of the city's oldest monuments, Porto Cathedral (Figures 2 and 3) is one of the most important local monuments. Construction began in 1170 in the Romanesque style. Gothic influences were added in the 14th and 15th centuries and then completed by 1737 with Baroque additions. Further modifications were carried out in the 20th century, along with a major restoration.

Figure 2 - Porto Cathedral

Figure 2 - Porto Cathedral

By Alvesgaspar - Own Work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=79290375

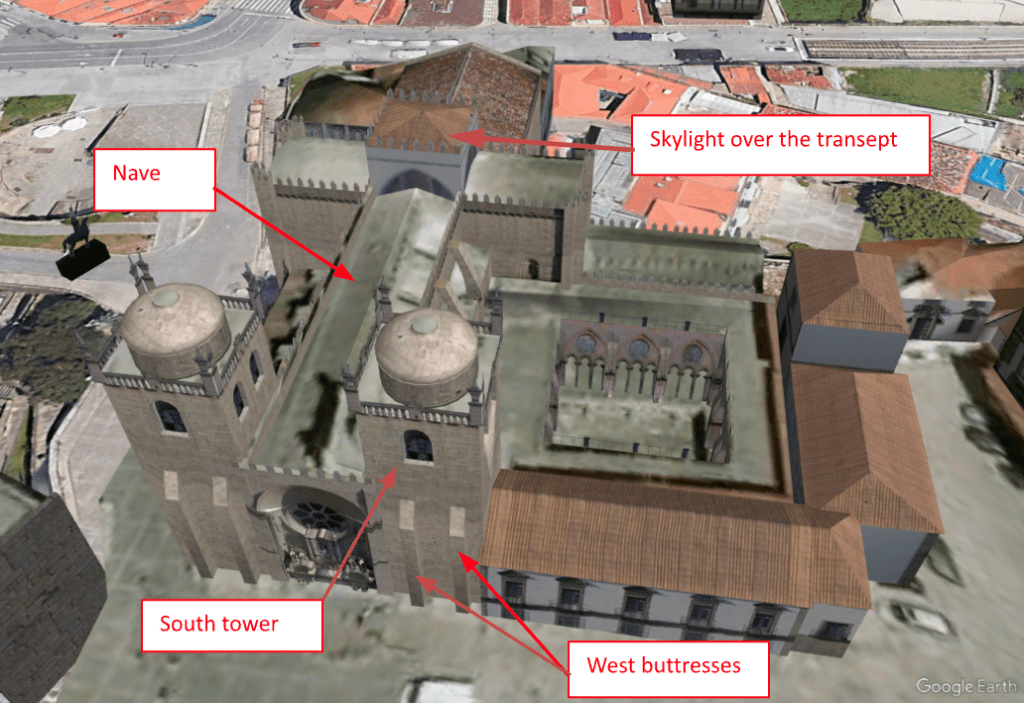

Figure 3 – Aerial View Courtesy of Google Earth Viewed From the West

Figure 3 – Aerial View Courtesy of Google Earth Viewed From the West

In Figure 2, we see the west elevation with the north and south towers. The towers, particularly the south, have been modified and strengthened over the years. The south tower was twice badly damaged by lightning and wind storms, and the upper half was rebuilt once.

While there were many recent restoration projects, I will highlight a few that were required to correct work done in the early 20th century. These include the south tower, the nave and the skylight, as seen in Figure 3. The graphics and information here are provided courtesy of P.B. Lourenco, L.F. Ramos, and K.J. Krakowiak in their paper Cathedral of Porto, Portugal: Conservation Works 2003-2008 from the 11th Canadian Masonry Symposium, 2009 (P.B. Lourenco et al.).

South Tower

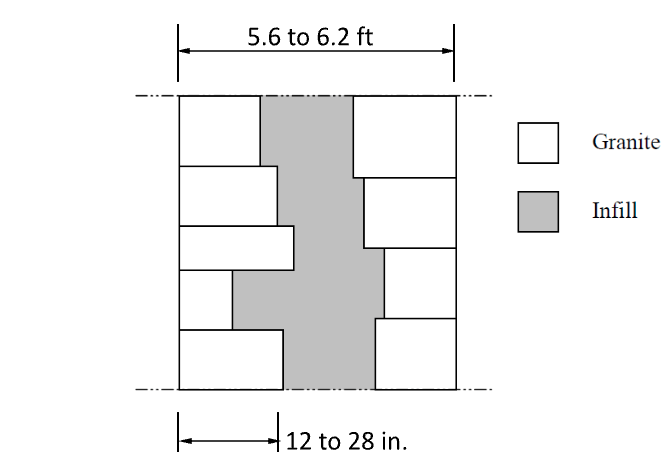

Both towers are approximately 33 square ft. and 115 ft. tall. The walls are constructed of granite-face stone, and rubble fill with loose stones and silty soil (Figure 4). The interior stairs and landings differ in each.

Figure 4 – Tower Wall Cross-Section By P.B. Lourenco et al.

Figure 4 – Tower Wall Cross-Section By P.B. Lourenco et al.

The south tower is particularly interesting because it was first completed in 1325; it did not match the north tower as it does today. It was damaged by lightning in 1552. The upper half was demolished and rebuilt In 1665-1669. Reportedly, the tower was close to collapse in 1717. The buttresses were added in 1727 to match the exterior of the north tower. The tower received another lightning strike before 1841.

In 2003, the tower was again in need of repair and strengthening. Both towers required repairs, but the south was worse. The restoration team discovered heavily weathered mortar joints near the top of the tower from rain events; the infill was wet. The cracks were solidified with lime grout injection. The 20th-century repairs used Portland cement mortar, which was removed, and the walls repointed using traditional lime mortar.

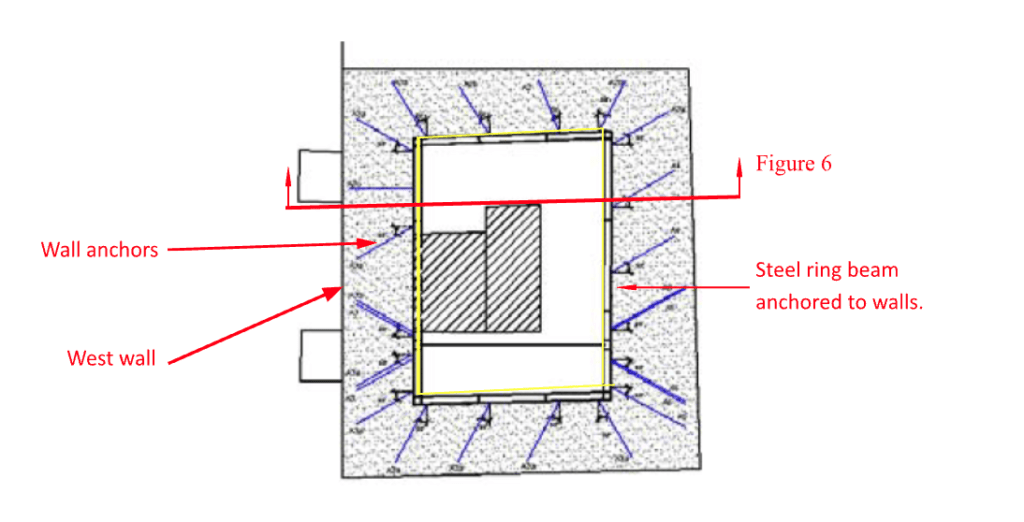

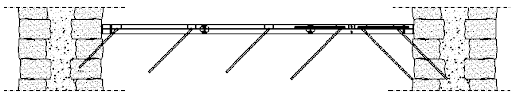

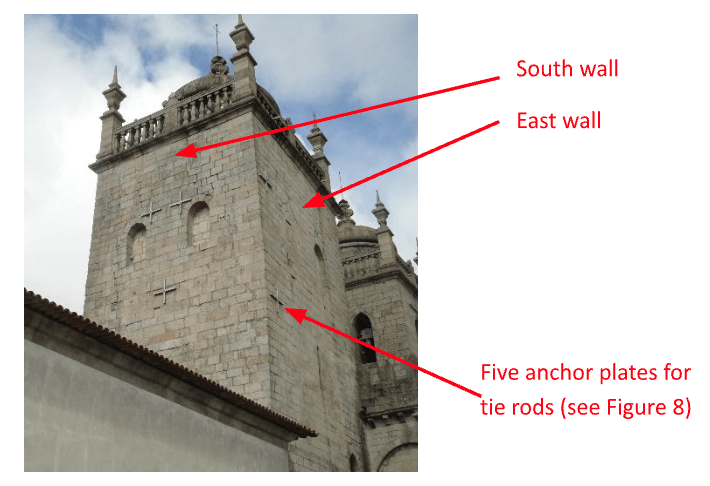

The major work of the towers was to strengthen the south and east walls that were bulging. Previous repairs installed tie rods, but these had corroded and broken, allowing the walls to continue to move. The restoration included adding a stiffening ring beam on the interior of the tower and anchoring the beam to the walls (Figure 5).

Figure 5 - Cross-section of South Tower by PB Lourenco et al.

Figure 5 - Cross-section of South Tower by PB Lourenco et al.

Figure 6 - Section of South Tower Showing Steel Ring and Anchors By PB Lourenco et al.

Figure 6 - Section of South Tower Showing Steel Ring and Anchors By PB Lourenco et al.

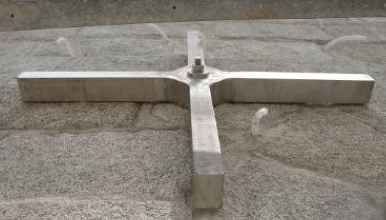

The broken tie rods were replaced with stainless steel rods, and additional ties were added. Figure 7 shows the south and east walls and the specially designed anchor plates for the tie rods designed as crosses, which had to be approved by church officials before they were installed. The tie rods between the east and west walls were drilled through the rubble portion of the walls.

Figure 7 - South Tower With Tie Rods Anchor Plates Shown

Figure 7 - South Tower With Tie Rods Anchor Plates Shown

Figure 8 – Cross-Shaped Anchor Plate

Figure 8 – Cross-Shaped Anchor Plate

Skylight Over The Transept

The skylight is built over the transept of the sanctuary (see Figure 9). Various cracks in the walls of the skylight can be attributed to the hipped roof structure. A ring beam was added on the interior at the roof eave to counteract the spreading of the walls.

Figure 9 – Skylight Viewed From the West

Figure 9 – Skylight Viewed From the West

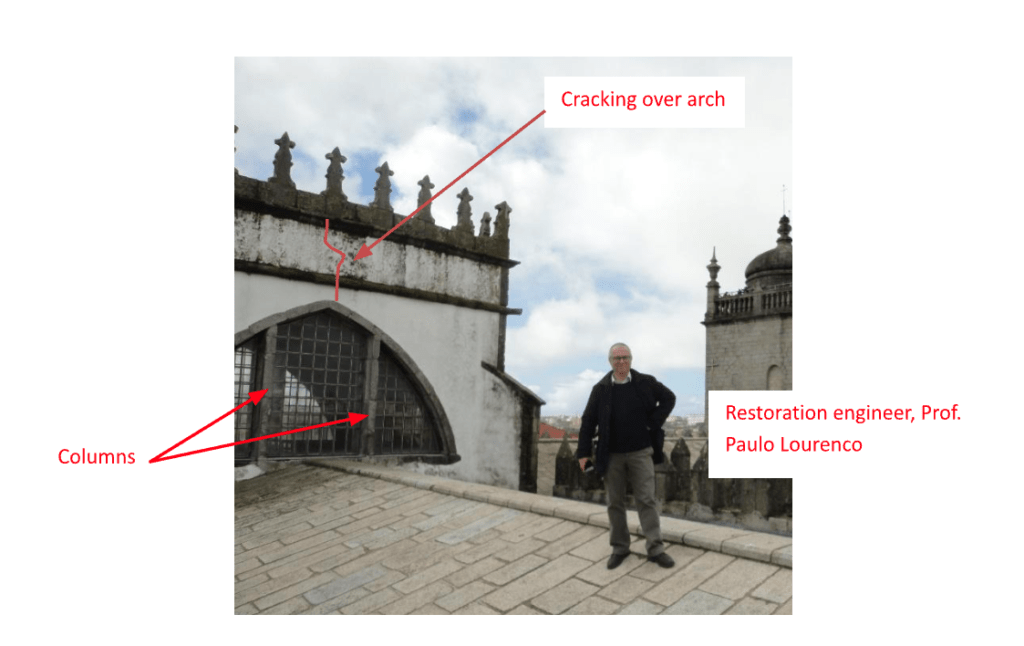

A significant finding was that the arched openings were not functioning as true arches, and cracks developed over the peak. The columns framing the windows (Figure 10) became load-bearing and interrupted the arching action, causing the cracking. Cracks were injected, roof load was removed, and the columns received supplemental framing

Figure 10 – Skylight Viewed From the North

Figure 10 – Skylight Viewed From the North

Nave

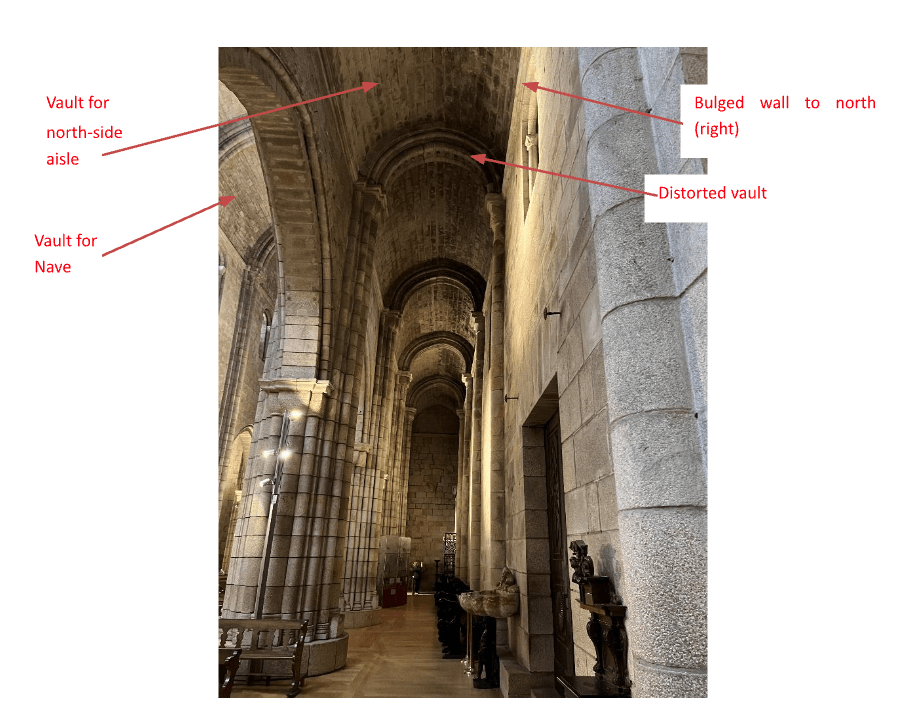

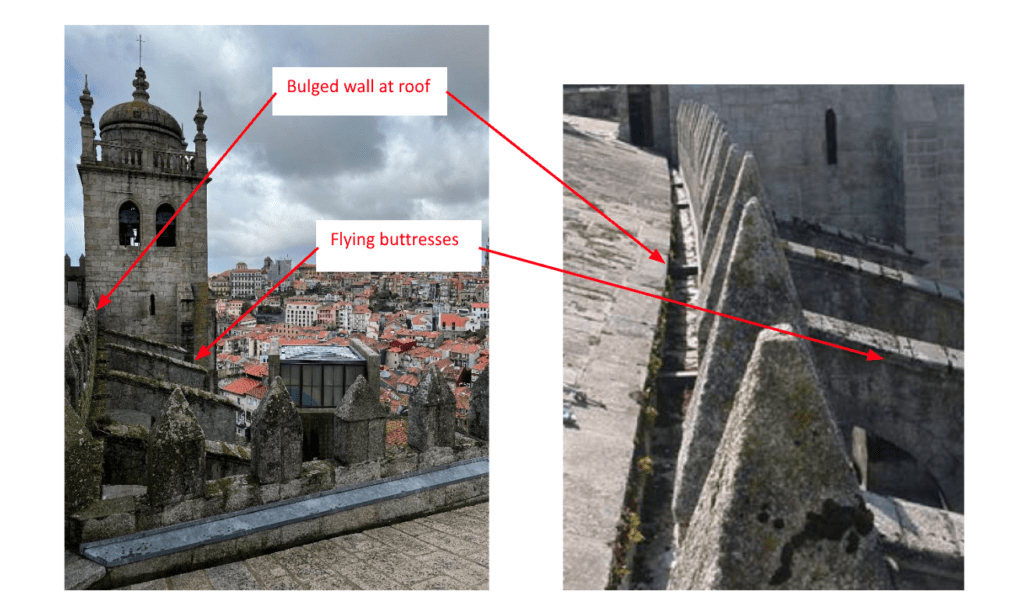

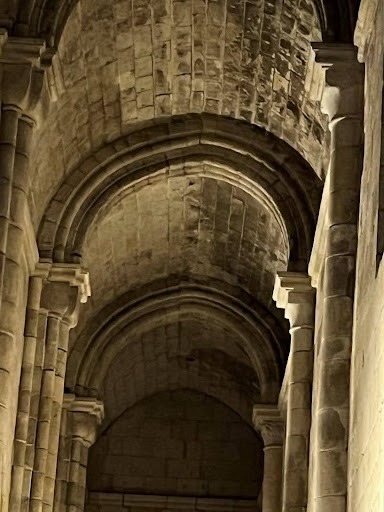

Throughout the cathedral, there are numerous signs of foundation settlement. The nave is supported by a barrel vault, as are the narrow side aisles. Figure 11 shows the north-side aisle. It’s not an optical illusion; the aisle vault is distorted, and the wall is bulged outward.

Figure 11 – North-Side Aisle of the Nave

Figure 11 – North-Side Aisle of the Nave

The bulge is surprising, considering the nave has flying buttresses for lateral support. Figure 12 shows the bulge on the north side; it occurs similarly on the south. The cathedral is unique in that it was one of the first in Portugal to have flying buttresses.

The assessment of the cathedral determined that the roof movement was primarily associated with foundation settlement. Figure 13 shows a closeup of the distortion at the north-side aisle vault due to the foundation movement. The cracks have been infilled with mortar and reinforced. Reportedly, the distortion has been this way for approximately 300 years. The walls are monitored for further movement. This example is amazing in that it shows the stability of an arch despite support movement.

Figure 12 – Bulged North Wall of Nave (Left); Closeup on the Right

Figure 12 – Bulged North Wall of Nave (Left); Closeup on the Right

Figure 13- Closeup of Vault Showing Distortion From the Settlement of Wall on the Right

Figure 13- Closeup of Vault Showing Distortion From the Settlement of Wall on the Right

Church de São Bento da Vitória

The church is a national monument and includes an attached monastery. It dates from the 1500s, and the monastery was completed by 1707. The walls are faced in Portuguese granite.

Figure 14 (left) shows the front façade in 2010 before restoration. In 2023, the façade was to be cleaned and repointed. Figure 14 (right) shows the façade scaffolding under cover during restoration.

Figure 14 - Church de São Bento da Vitória Front Façade 2010 (left); 2023 During Restoration (right)

Figure 14 - Church de São Bento da Vitória Front Façade 2010 (left); 2023 During Restoration (right)

Figure 15 shows the upper arch opening before the scaffolding was installed. Like the arches at the Porto Cathedral skylight, the arch here also has columns that disrupt the arching action of the masonry.

Figure 16 shows a graphic of the arch opening as built versus an ideal arch. While it’s desired that the full opening functions as an actual arch, it actually performs as segments of a curved beam whereby the window mullions and masonry columns provide the vertical support. This results in bending stress in the arch segments, overloading the window mullions (Figure 17) and causing them to buckle and stress the windows.

Figure 15 – Arched Opening

Figure 15 – Arched Opening

Figure 16 – Opening as Segments (Left); Opening as Desired (Right)

Figure 16 – Opening as Segments (Left); Opening as Desired (Right)

Figure 18 shows cracking at the right end of the center arch segment; the cracking occurs at both ends. While the arch segments overloaded the window mullions (Figure 17), the mullions still transferred sufficient loads into the masonry below the arched opening and cracked the masonry beam (Figure 19). Before the start of restoration, this damage was unseen. The restoration team planned to shore up the openings, remove the windows for their restoration, reinforce the arch segments and the lower masonry beam, and reinstall the windows with strengthening mullions.

Figure 17 – Window mullions buckled

Figure 17 – Window mullions buckled

Figure 18 – Cracking at Arch Segment

Figure 18 – Cracking at Arch Segment

Figure 19 – Masonry Beam Below Arched Opening (Viewed From Interior)

Figure 19 – Masonry Beam Below Arched Opening (Viewed From Interior)

Summary

Both the Porto Cathedral and Church de São Bento da Vitória are amazing examples of marvelous masonry in historic Porto. There are many more marvelous sites to visit. This article was only able to touch on a few highlights of the repairs and restoration efforts that have been ongoing. Without continual maintenance, history shows us that monumental structures often undergo significant restoration repairs on a 100-year interval. European experience should be considered by US restoration teams for their projects.

Acknowledgments

- I’d like to acknowledge my good friend Professor Paulo Lourenco of the University of Minho, who invited me and shared much of his work, and the added assistance of his staff with thanks to Ana Fonseca, Dr. Elisa Poletti, Dr. Daniel Oliveira, Dr. Alberto Barontini, and Dr. Vasco Bernardo, and support from the university.

- Support and assistance were provided by the Fulbright Commission Portugal from Dora Reis Arenga.

- Financial support was provided by the Fulbright Specialist Program thanks to Courtney Indart and Catherine Coats of World Learning.

About The Author

David Biggs is a US-based consultant and regular columnist for Masonry (Marvelous Masonry series) and Masonry Design (Technical Talk) magazines. He is a PE and SE with Biggs Consulting Engineering, Saratoga Springs, NY, USA (www.biggsconsulting.net), and an Honorary Associate Professor with the University of Auckland, NZ. He specializes in masonry design, historic preservation, forensic evaluations, and masonry product development. David was a Fulbright Specialist in Portugal in 2023.