Marvelous Masonry - Celebrating Masonry’s Heritage: Fort Ticonderoga

Words: David Biggs, Beth Hill, Miranda Peters, Matthew Keagle

Words: David Biggs

Photos Courtesy of Fort Ticonderoga Museum Collection

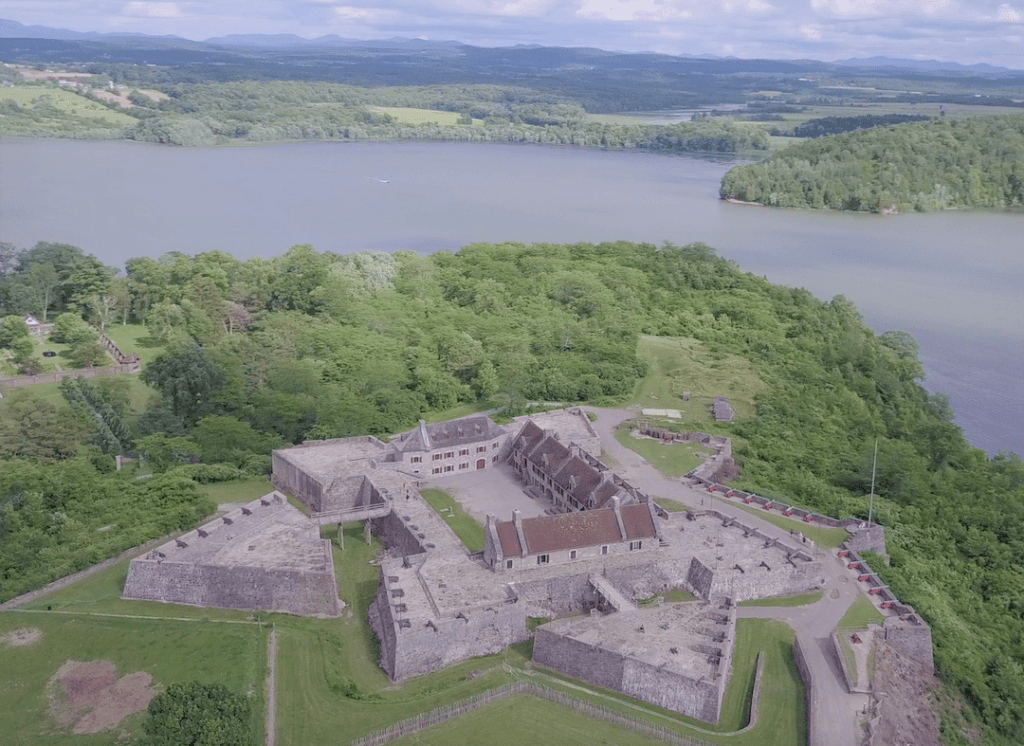

Europeans started colonizing the northeast United States in the 1500s and continued until the founding of the United States in 1783. Canada experienced similar colonization until it became a dominion in 1867 and finally an independent country in 1982. Throughout the colonial period, numerous marvelous masonry structures were constructed as fortifications or subsequently as monuments to conflicts. As we explore various historic sites in North America, we visit historic Fort Ticonderoga located in upstate New York at the southern end of Lake Champlain. Figure 1 shows a view of the fort with Lake Champlain and the Green Mountains of Vermont beyond.

Figure 1 - Fort Ticonderoga 2020

Figure 1 - Fort Ticonderoga 2020

Aerial view from northwest (courtesy of Fort Ticonderoga)HISTORY

In 1755, the French established an outpost of log work called Fort Vaudreuil. As the site grew in strategic importance, they designed and built Fort Carillon from 1755-1757 to defend against the British who controlled the south. It was the military key to the Champlain Valley.

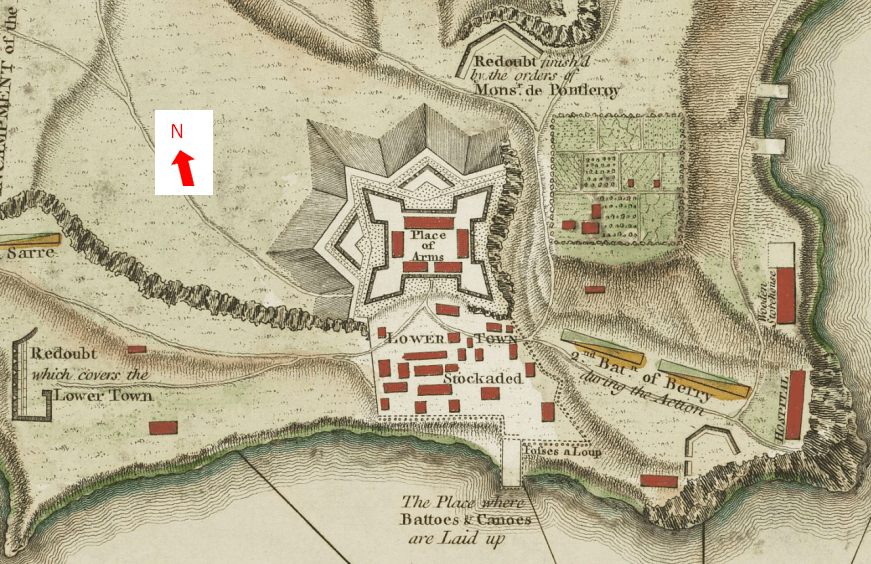

Figure 2 illustrates the fort in 1758 when it included three barracks housing about 400 soldiers, four storehouses, a bakery and a powder magazine (munitions warehouse).

The British gained control of Fort Carillon in 1759 during the French and Indian War (also known as the Seven Years War) and renamed it Fort Ticonderoga. However, upon leaving, the French destroyed the powder magazine and other portions of the fort. Despite British rebuilding efforts, records indicate the fort was still in terrible condition in 1773.

Figure 2 - Fort in 1758

Figure 2 - Fort in 1758The British surrendered control of the fort in 1775 when the colonists under Ethan Allen and the Green Mountain Boys along with Benedict Arnold captured the fort; this became the first American victory of the Revolutionary War. In an amazing effort during winter conditions, the fort’s cannons were then hauled to Boston and put into service to break the British siege. The Americans held the Fort Ticonderoga into 1777 but were again defeated by the British army.

The British formally evacuated the Fort after their defeat at the Battle of Saratoga in late 1777. Following this pivotal event in the American Revolution, the British presence in the region declined greatly. In the fall of 1781, they briefly returned to Fort Ticonderoga and partially rebuilt part of the West (Soldier’s) Barracks before the fort was fully abandoned for having no further military purpose. The American Revolution ended in 1783. New York State assumed the property in 1785 then donated it to Union and Columbia Colleges in 1803.

The story of the fort that we know today begins in 1820 when the property was sold to William Ferris Pell. The Pell family first used portions of the property, constructed a summer retreat, and also preserved the ruins of the fort. After 80 years, Pell’s descendants engaged Alfred Bossom, an English architect, to plan and oversee the fort’s initial phase of restoration so that it could be opened to the public. That initial phase was completed in 1909 and the opening ceremonies were attended by US President William Taft. The fort site quickly became a major tourist attraction. In 1931, the Fort Ticonderoga Association was formed to carry on the maintenance of the property. That maintenance continues today along with nearby historical landmarks Mount Defiance, Mount Independence, and portions of Mount Hope.

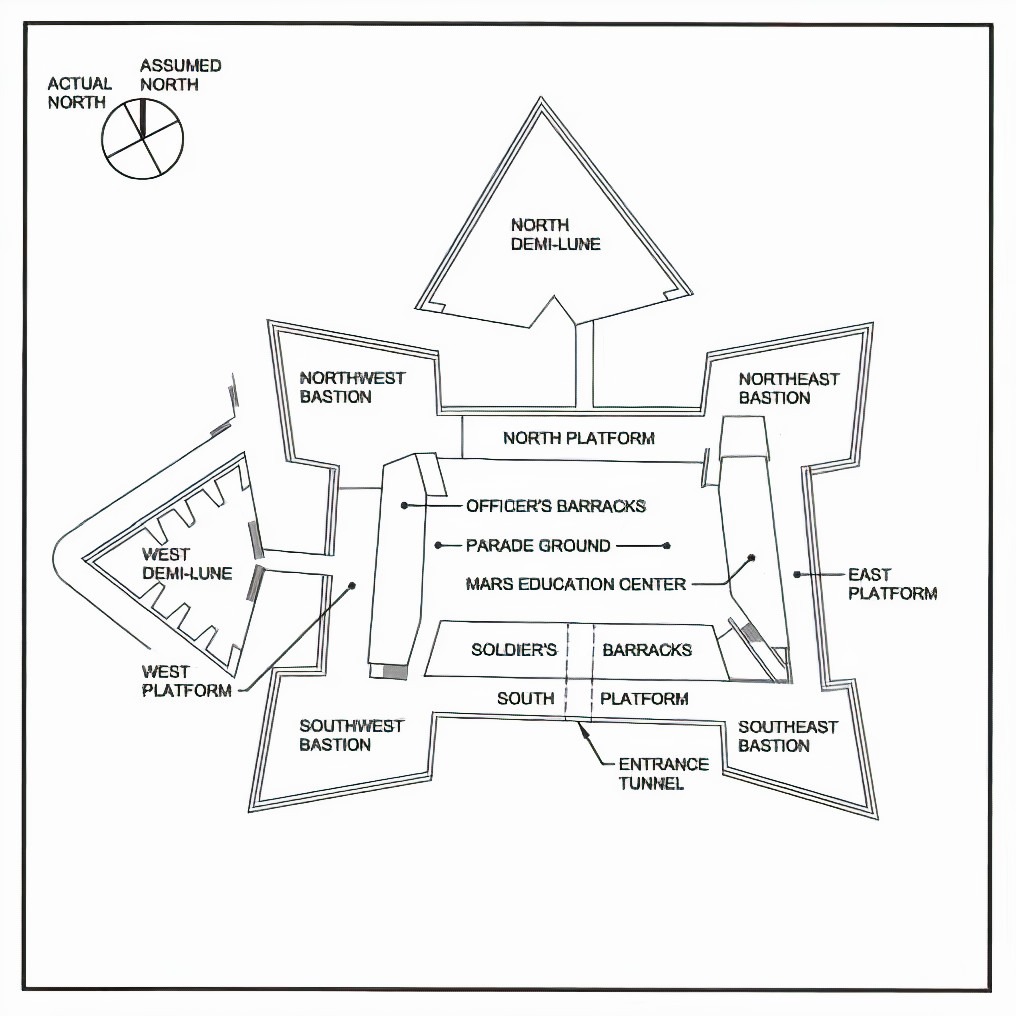

Today, Fort Ticonderoga is a museum, cultural destination, historic site, and educational organization. The Fort Ticonderoga Association preserves 2,000 acres of historic landscape on Lake Champlain as well as the fort itself, Carillon Battlefield, and the largest series of untouched Revolutionary War era earthworks surviving in America. Fort Ticonderoga was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1960. It has been a major cultural tourism attraction since its opening and is one of America’s Marvelous Masonry structures. Figure 3 provides the plan of Fort Ticonderoga today.

Figure 3 – Fort Ticonderoga 2020

Figure 3 – Fort Ticonderoga 2020MASONRY

To understand the masonry aspects of the fort, we go back to its construction. The French builders laid out the fort to the footprint we see today. In Figure 2, you notice the earthen walls on the north and west that were retained by horizontal logs.

The west, south, and east buildings and the demi-lunes were originally constructed of stone laid in mortar. The fort site had an outcropping of limestone that provided most of the building stone; additional stone was quarried from approximately one mile away.

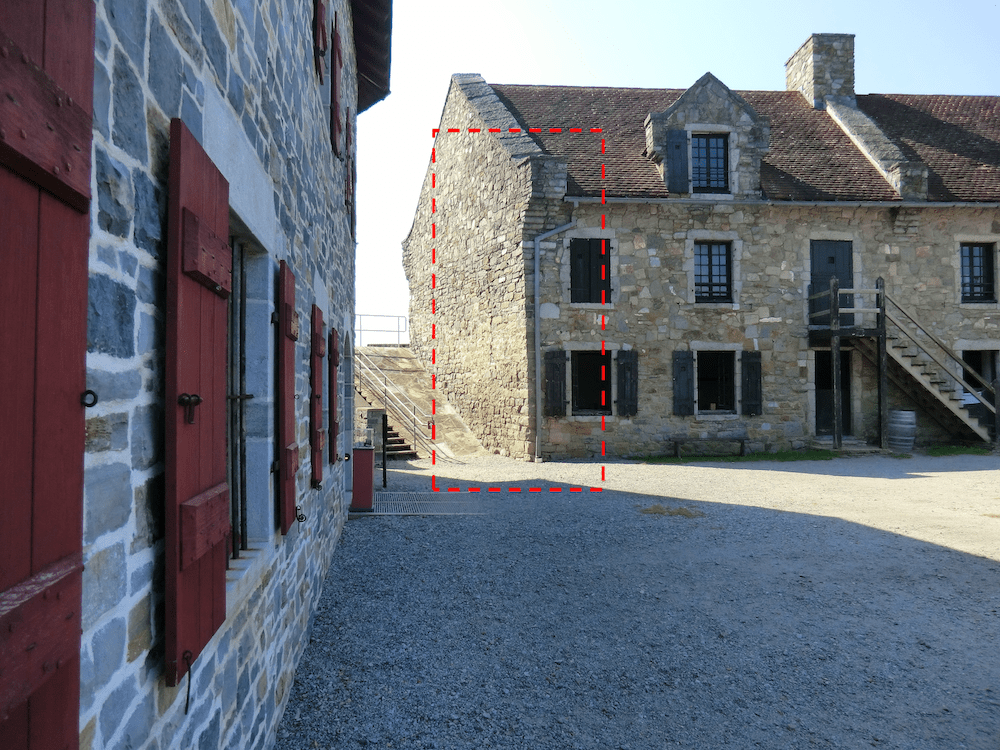

As previously mentioned, the French blew up the powder magazine that was under the southeast bastion when they abandoned the fort to the British. Much of the destruction was not rebuilt by the British. Figure 4 shows one view where the ruins are visible in the 1800s. A warehouse was in the lower left; the powder magazine would have been beyond that, the South Barracks in the center, and the South Barracks gable end is on the right. The current photograph (Figure 5) highlights a surviving wall of the South Barracks. The building on the left was reconstructed on the site just north of the powder magazine.

Figure 4 – Looking south toward the South Barracks

Figure 4 – Looking south toward the South Barracks Figure 5 – Original wall of South Barracks

Figure 5 – Original wall of South BarracksThe fort was constructed with random-coursed limestone quarried on site. Much of the fort is founded on limestone outcropping. Essentially, the fort became a ruin following the wars when much of the stonework was taken by settlers to construct homes and businesses in the region.

By the time the Pells decided to reconstruct the fort, the most significant portion of the fort to survive was the Officers’ Barracks (West Barracks). Figure 6 is taken looking at the West Barracks from the parade grounds before the 1909 restoration; it shows the remains of the barracks that were included in the restoration. These walls are incorporated into Figures 7 and 8.

Figure 6 – Ruins of West Barracks before 1909 reconstruction

Figure 6 – Ruins of West Barracks before 1909 reconstructionThe restoration completed in 1909 was extensive but did not include the entire fort. Where possible, constructors incorporated existing masonry into the work. The next photo from 1915 shows the restored West Barracks (Figure 7). Figure 8 shows the West Barracks today. The Soldiers Barracks (South Barracks) were not rebuilt until 1931.

Figure 7 – West Barracks after 1909 reconstruction

Figure 7 – West Barracks after 1909 reconstruction  Figure 8 – West Barracks 2020

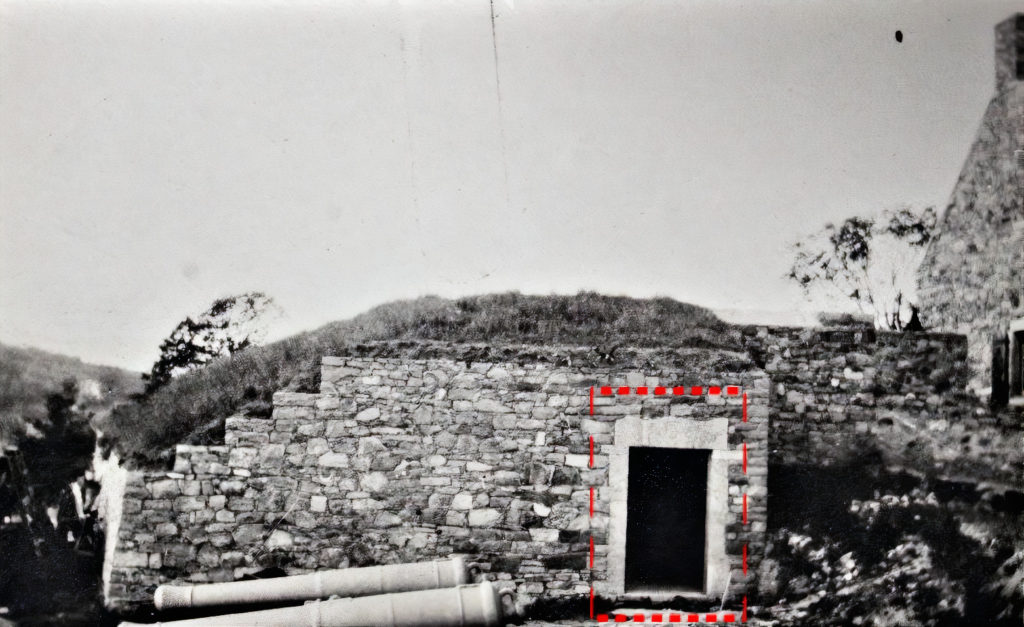

Figure 8 – West Barracks 2020The original fort had earthen-filled bastions and curtain walls retained by logs. 20th-century reconstruction introduced stone walls (Figure 9) and steel framing to create storage spaces below. The reconstruction further extended the curtain walls higher to create platforms for the cannons (Figure 10). The “ghost” of the door in Figure 9 is still evident in the current construction.

Figure 9 – Southwest Bastion 1909

Figure 9 – Southwest Bastion 1909 Figure 10 – Southwest Bastion 2020

Figure 10 – Southwest Bastion 2020The South Barracks were not reconstructed until 1931 (Figures 11 and 12). It is notable that this building has not required significant restoration since then.

Figure 11 – South Barracks viewed from the north

Figure 11 – South Barracks viewed from the north  Figure 12 – South Barracks viewed from South Platform

Figure 12 – South Barracks viewed from South PlatformThe 1909 restoration was developed by a British architect so the fort presents itself primarily as a British fort since. However, in 2008, The Deborah Clarke Mars Education Center was opened. It sits on the original site of the French Magazin du Roi, better translated as the “King’s Storehouse”. The building was designed by architect Andrew Wright of Tonetti Associates (now Starboard Architects). One floor plan of the original second-story survives at the New York Historical Society and was used to inform the foot-print of the reconstruction. The overall architecture is French-inspired (Figures 13 and 14) based upon other fortifications of the period.

Figure 13 – Mars Education Center viewed from North Platform

Figure 13 – Mars Education Center viewed from North Platform Figure 14 – Mars Education Center viewed from East Platform

Figure 14 – Mars Education Center viewed from East PlatformRestoration is an on-going need to maintain historic sites. Figure 15 shows the most recent reconstruction of the southeast bastion that was part of the Mars project. Figure 16 shows the northwest bastion with some significant loss of face stones; the bastion currently is scheduled for repairs.

Figure 15 – Reconstructed Southeast Bastion

Figure 15 – Reconstructed Southeast Bastion Figure 16 – Northwest Bastion awaiting restoration

Figure 16 – Northwest Bastion awaiting restorationLooking at the fort as a whole is impressive. However, there are subtle details that truly make the masonry marvelous! One example is the corbelling. Figure 17 is a dormer on the West Barracks. Figure 18 is the southwest corner of the South Barracks with corbelling on the end wall and the dormer. The craftsmanship of the stonework is excellent; the corbel overhangs exceed the current industry standards for masonry construction and are performing perfectly.

Figure 17 – Dormer corbelling on West Barracks

Figure 17 – Dormer corbelling on West Barracks Figure 18 – Corbelling on South Barracks

Figure 18 – Corbelling on South BarracksFigure 19 shows end wall corbelling on the West Barracks from 1909. The Mars Center (2008) was designed with its own corbelling (Figure 20).

Figure 19 – End wall corbelling on West Barracks (c. 1909)

Figure 19 – End wall corbelling on West Barracks (c. 1909) Figure 20 – Corbelling on Mars Center (2008)

Figure 20 – Corbelling on Mars Center (2008)Another wonderful detail includes the anchoring of the stone coping on the tops of the gable ends. Figures 17 and 19 also show examples of using horizontal stones to restrain the sloping copings. Figure 21 provides a close-up. The slope helps shed water naturally. Another historic means for creating copings uses metal (see Figure 20); these too shed water and protect the walls below. Interestingly, many newer buildings use stone copings that are anchored or pinned to the wall below without the horizontal stones (Figure 22 from a church in Bennington, VT). These copings are prone to leaking into the top of the joints and damaging the walls.

Figure 21 – Horizontal coping stones

Figure 21 – Horizontal coping stones Figure 22 – Anchored coping stones

Figure 22 – Anchored coping stonesAnother great stone feature is the variability of the stone lintels. Figures 23a through 23e show the different types of lintels and jamb stones that provide a unique character to the buildings. The random-coursing of the stone allows for the variable lintel, sill, and jamb stone sizes in Figures 23a through d. Figure 23e shows the Mars Center lintels, sill, and jambs are fabricated from more regular cut stone.

Figure 23a

Figure 23a Figure 23b

Figure 23b Figure 23c

Figure 23c Figure 23d

Figure 23d Figure 23e – Mars Center

Figure 23e – Mars CenterFigures 23a through 23e – Lintels and Jambs

Finally, monumental masonry often includes significant arches. The entrance to the parade grounds those arches (Figures 24 and 25). The rise and depth of the arches are well proportioned for the openings. The exterior arch supports the opening in the South Curtain wall and portions of the cannon-bearing platform (terreplein). The arch is more susceptible to cracking from water infiltration through the platform.

Figure 24 – South arch entrance viewed from the exterior

Figure 24 – South arch entrance viewed from the exterior Figure 25 – North arch viewed from the parade grounds

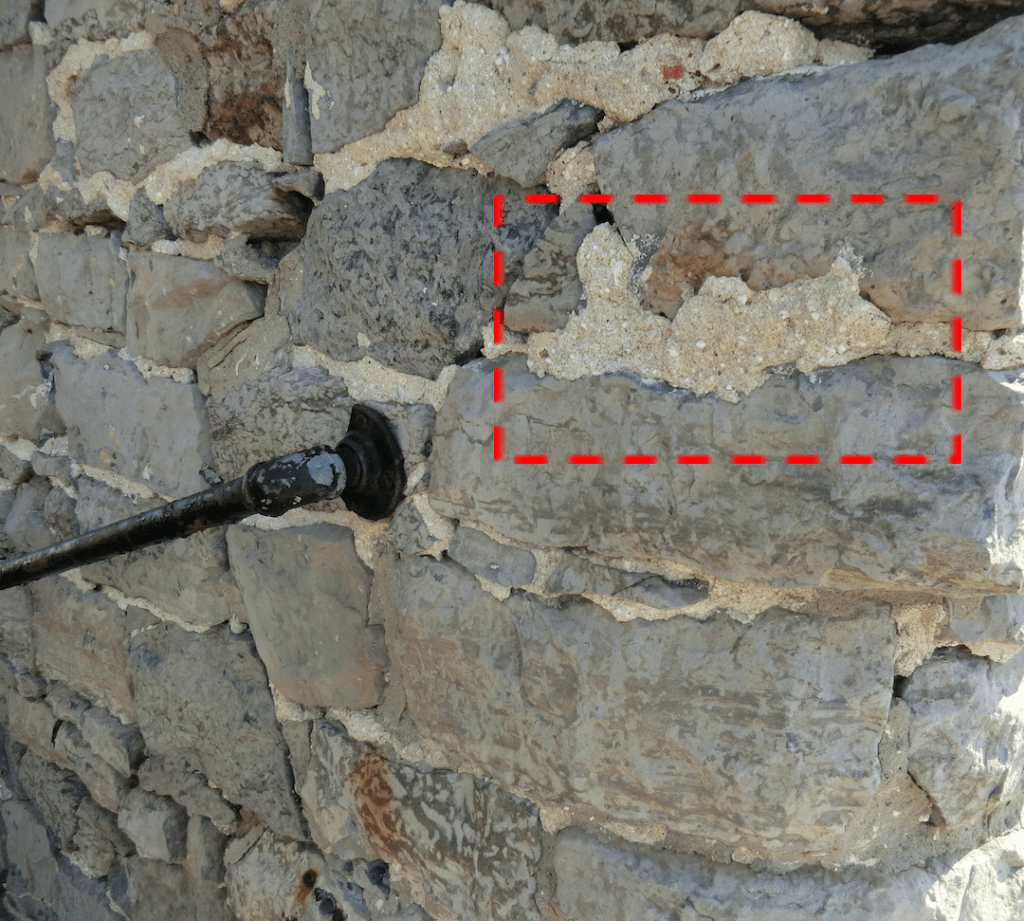

Figure 25 – North arch viewed from the parade groundsThe original mortar was lime-based and had ground up shells in the mix (Figures 26 and 27). There are visible lime pockets in the original mortar. There are locations where the original mortar is intact and functioning well; in other locations, the mortar eroded and the joints were repointed.

Figure 26 – Original mortar on South Barracks 2020

Figure 26 – Original mortar on South Barracks 2020 Figure 27 – Enlarged view of the original mortar

Figure 27 – Enlarged view of the original mortar Since the reconstruction in 1909, the mortar has generally been Portland cement-based Type N for better durability; it is usually grey in appearance.

SUMMARY

Every marvelous masonry site has a place in history. Fort Ticonderoga is exemplary! Although much of what tourists see is a re-creation, the stone fort is a monument to our past and an example of the enduring qualities of 18th-century construction.

Maintaining any historical site is a challenge due to obtaining sufficient funding. Previous repair campaigns were performed at Fort Ticonderoga in 1925, 1928, 1930, 1940, 1976, and 1985. A plan was established in 1992 for prioritizing major repairs. Current efforts to complete the plan have been on-going since 1996 with diversions due to modified priorities and funding. A new round of restoration of portions of the walls was set to begin in early 2020, but has been delayed due to the pandemic.

Historical sites such as Fort Ticonderoga deserve our support. Plan a trip for “One Destination, Endless Adventures” (https://www.fortticonderoga.org/). You can also enjoy the fort’s digital opportunities (fortticonderoga.org/learn-and-explore/center-for-digital-history/).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

My thanks to Beth Hill, President and CEO of Fort Ticonderoga; Miranda Peters, Vice President of Collections & Digital Production; and Matthew Keagle, Ph.D., Curator, for their stewardship of the fort, valuable assistance, and access to many of the images. Historic images are credited to the Fort Ticonderoga Museum Collection.